Can Transit Oriented Development be effective in Urban India?

The concept of Transit-Oriented

Development (TOD) as a planning tool is new to Indian cities, where quality

mass rapid transit systems (MRTS) are a recent development. The idea of TOD has

emerged due to the steep rise of congestion and poor air quality due to rapid

urban development experienced in the last decade. Delhi, in particular, is

looking to TOD as a solution to its mobility and air quality issues. The city

recently prepared a TOD policy document that it will apply around Delhi Metro

stations. TOD is being championed by UTTIPEC (Delhi Development Authority) as a solution to congestion, environment quality and housing equity. Global

sustainability proponents are also encouraging TOD as a tool to achieve greater

sustainability in the developing world, avoiding the costly mistakes of cities

in industrialized West. TOD seems to be a win-win solution for local concerns

and global sustainability. Can this concept, developed for the auto-dominated

North American city, be universal enough to be applied in urban India?

The primary goal of TOD is to shift

an auto-centric realm of urban living to a transit-centric realm of urban

living. The main indicator of a city’s auto or transit orientation is the mode

share – the proportion of daily trips being made by private vehicle transportation

versus other public or non-motorized transport (NMT) means. If private vehicular

modes of transportation constitute a major share of trips, TOD interventions aim

to significantly shift the mode share.

The TOD guidelines for Delhi indicate a desire to achieve a 70-30 modal share

(public-private) in favor of public transportation by 2021[1]. How does the mode share of Indian

cities compare with other cities around the world? Do Indian cities have

significant numbers private vehicle trips to easily shift to mass transit?

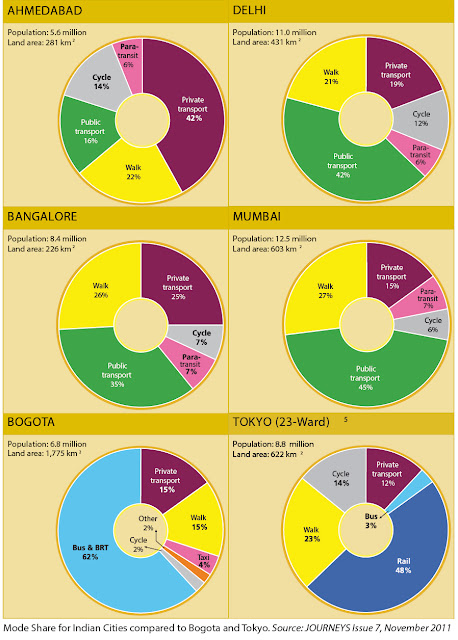

A 2011 comparison study in the

journal Journeys[2]

of the mode share in select global

cities with over a million residents included Ahmadabad, Bangalore, Delhi and

Mumbai. The study indicated the Indian metros except Ahmadabad have 25% or less

mode share for private transport.

Only Tokyo (comparable in land area and population to Mumbai & Delhi), had

a lower private transportation share at 12%. Going by the Journal’s report,

Delhi already has a desirable mode share

with only 19% of private transport trips. In addition, the Delhi metro

ridership is at an all-time high at 2.4 million passengers a day[3].

So can a TOD policy focused around Metro stations be effective in shifting the

mode-share from cars to transit? Or will intensification add to the congestion?

This comparison indicates that Indian

metros need to contextualize their TOD policies, if they aim to move automobile

commuters to public transit. Looking at Indian cities, the potential for

significant mode share shift would be

in Ahmadabad (42% private transport) and Bangalore (25% private transport). TOD

strategies in Delhi and Mumbai would need to focus on making existing

localities more amiable to non-motorized travel, and; focusing TOD strategies

judiciously along transit corridors, by understanding travel relationships

between trip originations and destinations.

To be effective, TOD policy formation

should begin with setting quantifiable benchmarks that best represent the

objectives and goals of the city. While shifting the mode share is a prominent TOD benchmark, other benchmarks should

also be considered, especially for Mumbai and Delhi, where the mode share already is quite favorable. Benchmarks

that quantify the following strategies can be utilized to measure the success

of TOD policies:

·

Matching land

use capacity along transit corridors to the MRTS capacity – This approach would be most effective for cities where a

singular Mass transit system is being utilized for a TOD strategy. This will

help create an optimum density along the corridor, and avoid congestion that

may arise due to over intensification along the corridor.

·

Identifying

existing transit rich areas

–Existing neighborhoods with high public transit density should be candidates

for TOD strategies to match the transit capacity. Transit stations areas that

have multiple modes of transit such as regional rail or BRT could have much

higher densities beyond what would have been dictated by the previous

benchmark.

·

Setting land

use mix goals for neighborhoods and districts – A diverse mix of land uses is the cornerstone for

pedestrian and transit-oriented community. A benchmark for a desirable use mix

would measure existing transit supported single use neighborhoods changing over

time and attain the desired mix without necessarily intensifying beyond an

optimal density.

·

Setting

benchmarks for increasing cycle/rickshaw infrastructure – Rather than focusing on a private to public travel

mode-shift, settings goals for increasing NMT modes could be more effective in

changing travel habits. It has been evident in many cities, where proper

investments are made in pedestrian/bicycle infrastructure, more people use it.

Bogota, Copenhagen, Portland, Curitiba are prime examples of this.

·

Identifying TOD

ready areas – Old, resettlement and traditional

neighborhoods may already have ‘good bones’ for becoming a TOD with good street

connectivity, use-mix and density. By adding transit connectivity, and minimal

infrastructure interventions, they could become transit-oriented.

·

Setting a

benchmark for affordability along the corridor – One of the goals set by DDA’s TOD policy is housing for all [4]

by mandating affordable housing be part of any new project within the TOD zone.

Affordability in urban metros should include the cost of housing and

transportation. If redevelopment of existing slums is part of a TOD project,

the resettlement should account for both the cost of housing and transportation

from the new housing to the existing job centers of the displaced residents. If

the cost rises beyond an established benchmark, alternatives should be

considered.

These

strategies, though not comprehensive, are crucial for making TOD successful in

urban India. Setting benchmarks for these contextual strategies will provide

targets that city planners and administrators can aim for by appraising policies,

strategies and projects periodically to ensure the city is transforming from being auto-dominated to a more equitable multi-modal oriented environment.

Note:

- A more generalized version of this blog is posted at theCityFix.com - here

- The Institute for Transportation & Development Policy(ITDP) has recently published a set of TOD standards that provide key metrics for creative good TOD projects. These metrics could be a good starting point for customizing Indian TOD strategy benchmarks.

[1]

UTTIPEC (2012). Transit Oriented Development – Policy, Norms, Guidelines pp. 3

[2]

LTA Academy (2011). Passenger Transport Mode Shares in World Cities. Journeys,

Issue 7 pp. 60-71. Website: http://ltaacademy.gov.sg/doc/JOURNEYS_Nov2011%20Revised.pdf

[3]

The Economic Times (August 10, 2013). Delhi Metro sets ridership record with

over 25 lakh commuters. Website: http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.com/2013-08-10/news/41268141_1_ridership-record-delhi-metro-thursday

[4]

UTTIPEC (2012). Transit Oriented Development – Policy, Norms, Guidelines pp. 3

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete